Categorizing Across Social Groups

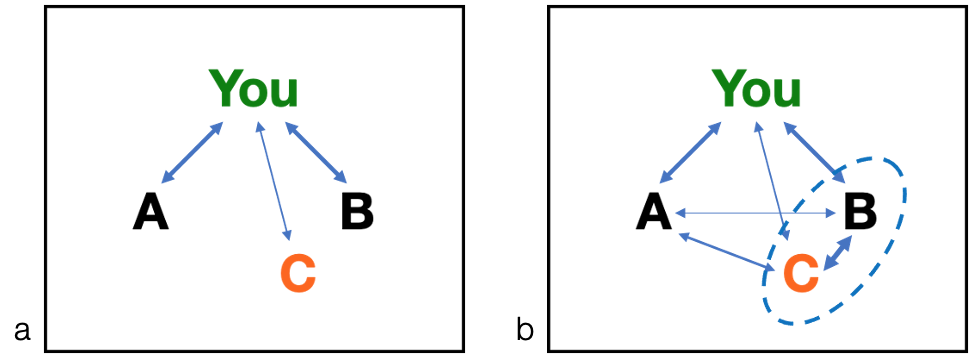

How do we learn social group boundaries and categorize others into "us" and "them"? Previous research relied on explicitly labeled, static groups (e.g., team membership, race, gender, etc.) and suggested that we infer others’ group membership via dyadic similarity—specific, static, salient features we share directly with others. In other words, “How similar am I to Annie?” drives how we perceive Annie, and “How similar am I to Betsy?” drives how we perceive Betsy, but “How similar am I to Annie?” does not affect our perceptions of Betsy (Fig. 1a). Thus, sharing the same skin tone with another person may indicate in-group membership and their choices may influence our own choices. Dyadic similarity can also be found in other fields; basic spatial voting models suppose that voters select the political candidate with whom they directly agree the most. Similarly, social influence is frequently operationalized as propagating through the direct ties in large networks.

In contrast, we use a generative model of Bayesian latent structure learning, in which we glean information from the environment to infer the most probable latent group of people. We can integrate across the relationships between everyone in addition to how each each person relates to ourselves. Asking “How similar am I to Betsy?” and “How similar am I to Annie?” and “How similar are Annie and Betsy?” drives how we perceive Annie and Betsy because they affect which latent groups (or structures) are inferred (Fig. 1b). Someone who is inferred as an in-group member in one context may be an out-group member in another context.

These latent groups affect trait attributions made about agents, and their effects persist despite explicit group labels that contradict the latent group. Moreover, separate areas of the brain concurrently track probabilities from the latent structure model and forms of dyadic similarity. In forthcoming work, we adapt the model into a novel, scalable framework to detect latent communities in large data sets that may otherwise be undetectable given current methods. We illustrate the framework’s utility by applying it to longitudinal mobility, communication, and friendship data observed from a large community over a nine-month period. Taken together, this suggests that the flexibility and context-dependent nature of understanding “us” and “them” can be captured by a latent structure model. Reframing social groups as a form of latent group learning has implications for understanding and modelling intergroup processes, social influence, and choice behavior across different fields.

Yet, perhaps when we actively categorize in- and out-group members, we rely on dyadic similarity, and this process may then be associated with regions of the brain commonly associated with thinking about our own and similar/close others’ states, traits, and characteristics. However, we find that active in-group categorization may instead rely on goal-oriented, domain-general networks in the brain.

A recording of a seminar presentation covering some of this line of work can be found here.